Transparency was the key discussion point at last week’s Sustainable Seafood Symposium hosted by Seafood Legacy in Tokyo with more than 1,000 attendees, where Planet Tracker spoke on two panels.

In revising its Fisheries Act in 2018 for the first time since 1949, the Government of Japan introduced scientific baselines for most commercial fishing species while opening doors for private sector investment enabled by a $2 billion increase in public spending to support this transition towards scientific management of domestic fisheries.

The Japanese domestic wild-catch seafood industry is now required to comply with the Act by transparently reporting where it fishes, what it fishes and how those fisheries are sustainably managed. The Act now states “ensure sustainable use of marine resources”.

With 41 publicly traded companies worth $134 billion in the fisheries sector in Japan, the Japanese seafood industry is the 6th largest source of international trade for Japan, right behind electronics. Overall, the Japanese seafood industry accounts for 2% of Japan’s exports and imports respectively, making the seafood industry critical to supporting the country’s GDP growth, macroeconomic stability and sovereign health.

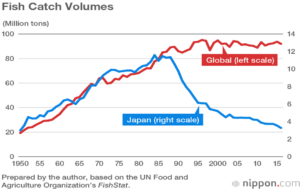

For example, as shown below, Japan’s wild-catch fish volumes have declined 74% from 12.8 million tonnes in 1985 to 3.3 million tonnes in 2017.

The Fisheries Act enables investors and lenders, with their $134 billion investment in the industry, to ask for seafood sourcing information such as cash flow from operations, sources of revenue and costs of goods sold from the 41 companies they finance. As shown below, compliance with the Act means that, if companies have direct or indirect ownership exposure, they need to disclose the scientific baselines for the fisheries they work, their total allowable catch based on a maximum sustainable yield model and their individual tradeable quotas.

This transparency is key for lenders in the sector as it informs loan covenants. It also helps asset owners and asset managers choose how to invest in the sector, whether through integrating this financial information into models, or informing positive or negative screening of the 41 companies in the sector.

![]()

The revised Act is good for Japanese business and its critical contribution to the Japanese economy. As Japanese investors scale back their investments in coal and address investments in palm oil, they are also beginning to assess their exposure to declining seafood stocks and their responsibility to invest in companies that manage their operations by applying scientific principles.

Given this, the Act enables transparency making it easier for investors to align their capital with companies who are managing their resources responsibly. This transparency will support the reversal of decades of declining domestic fish stocks by applying scientific principles to most commercial fisheries. Finally, financial transparency is key for the Japanese seafood industry to remain competitive and maintain its role as a global leader in industry.