The listing of approximately 8% of Raízen for R$ 7 billion (USD 1.4 billion) looks imminent. How will sustainable investors view one of Brazil’s largest stock market listings to date? Raízen’s energy interests promote low emission ethanol as well as biogas and cogeneration, demonstrating the capital expenditures of an energy company in transition. It embraces sustainability standards ranging from GRI and SASB to emission monitoring with CDP. It looks like a one-way bet until you switch away from ‘climate lensing’. Should we be using arable land to grow biofuels? Should we be encouraging rising sugar consumption? From a food system viewpoint, the company doesn’t look so sweet. How will the capital markets price Raízen in early August?

What is Raízen?

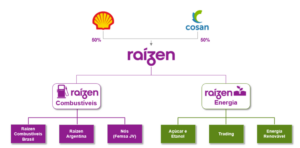

Raízen[1], founded in 2011, is a 50/50 joint venture between Shell and Cosan. Cosan[2] is a holding company with a portfolio of products ranging from ethanol, bioenergy, natural gas and lubricants to logistics, notably railways, and sugar production and trading.

Raízen has four main business lines. Its renewables activities include ethanol, biogas, cogeneration and energy trading while marketing and services, through the Shell brand, covers fuel distribution (including B2B), service stations and aviation. Under its ‘proximity’ label it includes its convenience stores under the Oxxo and Shell Select brands.

The structure of Raízen

Source: Raízen

Raízen’s main interests are located in Brazil and Argentina although it trades globally with offices in the Philippines, Singapore and Switzerland. It has a wider geographical presence with its Oxxo stores throughout Latin America.

Its shareholders have announced their intention to partially float the company in a listing[3], presently believed to be approximately 8% of the company[4]. This will be one of Brazil’s largest initial public offerings (IPOs) this year so is likely to attract widespread investor attention. However, there will probably be an interesting discussion about its sustainability qualities and whether its equity deserves a green valuation premium.

Sustainability credentials

Raízen’s GhG emissions are high, at 40.8mn CO2 in 2019 (scope 1, 2 and 3, of which 1.4mn is in scope 1)[5]. As a country, Brazil emitted 465.7mn tonnes of CO2 in the same year[6].

Still, at a corporate level, the company pushes relatively hard on the ESG agenda. It publishes annual sustainability reports of its operations in Brazil and Argentina. It makes nine ESG commitments which cover issues such as reducing its carbon footprint of ethanol and sugar by 10% by 2030 compared to 2018-19, reducing its water intake by 10% over the same period (in 2019, its water withdrawal totalled 51 billion litres)[7], and ensuring traceability of all of its crushed cane[8]. Reporting in line with Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines, it has recently included indicators from the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).

The company also responds to the CDP Climate Change questionnaire annually achieving an ‘A minus‘ grade, placing it in the leadership category[9]. More recently, management has announced it is working towards the TCFD guideline. This focus on climate change makes sense for a company which has been affected by drought in the past. Previously it has shut down and delayed production at some of its mills[10], [11].

Relative to many energy companies, Raízen’s sustainable qualifications look superior. The company is self-proclaimed as a ‘true green champion’, arguing it is ‘a global benchmark in bioenergy’ which is ‘leading the energy transition and reshaping the future of energy’[12].

Raízen’s renewable credentials include fuels such as ethanol, second generation ethanol (E2G), produced from bagasse[13] from the production of sugar, regular ethanol – biogas, which is converted into electricity and biomethane, and power generation from biomass and renewable (solar) sources. Although, as we have noted above, it also sells the more traditional oil products such as gasoline and jet fuel, it can argue that it is assisting with the energy transition. Its CEO comments that ‘biogas and second-generation ethanol (E2G) [are] our two big bets for the future’[14].

By examining Cosan, one of the joint venture owners, we can obtain an idea of the indices that will be considering Raízen, depending on their free float rules. We would expect Raízen to wish to be included in such sustainable indices.

Cosan’s index participation

Source: Cosan

So, what is there not to like?

If we move away from the energy ‘climate lensing’ perspective and view the operations of Raízen from a food system viewpoint, some uncomfortable issues emerge. In our recent blog, ‘Time to move beyond climate lensing’, we argued for an integrated climate and nature approach.

Raízen has a cultivated land area of 870,000 hectares – in relative terms, close to two-thirds of Belgium’s total agricultural land area[15]. We recognise that E2G does not require additional farmland as it uses agricultural waste products. However, sugarcane requires dry, hot land and therefore cannot be grown in the Amazon rainforest or the adjacent Pantanal swamp land, but it can displace other activities such as cattle farming to these areas, indirectly leading to deforestation. In addition, sugarcane production is extremely water-intensive and can pollute freshwater ecosystems with silt, fertilisers, plant matter and chemical sludge from mills[16].

We should also be mindful of the world’s ability to feed a growing population. Recently the FAO has stated that Sustainable Development (SDG) Goal 2 – achieving zero hunger by 2030 – is in doubt[17]. The latest edition of the ‘State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World’ (2020)[18] estimates that ‘nearly 690 million people are hungry, or 8.9 percent of the world population – up by 10 million people in one year and by nearly 60 million in five years’.[19] Looking at land use from a narrow climate viewpoint is a dangerous path to follow.

There has also been an ongoing debate about the relationship between biofuel cultivation and food prices. Opinion is divided. In 2017, the European Commission’s Renewable Energy Progress Report stated that ‘EU ethanol consumption had negligible impact on cereal prices’[20]. Soon after its publication, a metadata analysis of over 100 economic models by Cerulogy concluded that ‘food-based biofuels do lead to increases in food prices’[21]. What is clear is that regional variations and feedstock type need to be taken into account.

Furthermore, Raízen’s agricultural production is focused on sugar. It is one of the largest exporters of sugar globally, producing 8.3 million tons of crushed cane in the year ended March 2021.

This sugar has three main destinations: food (including refined sugars, chocolate, cakes, cereals and ice cream), pharmaceutical (notably for syrups) and beverages (such as soft drinks, juices and energy drinks).

It is increasingly recognised that sugar is a major contributor to obesity and diabetes and that sugar consumption is rising in most countries, especially amongst children and adolescents[22]. An estimated 40 countries have now implemented sugar taxes on sweetened beverages which started as an import tax for some small island states, but later was instituted as a specific product tax in countries such as Finland (2011) Mexico (2014), Mauritius (2016) and the Philippines (2018)[23].

The sustainable dilemma

Soon the equity markets will be pricing a company which is more sustainable than many of its energy peers when viewed from an energy and emissions perspective. To add spice, one of the joint partners is Shell and no doubt it will be viewing this listing as an indicator of how the markets price energy transition plays.

For those focused on the food system it’s a different picture. Are biofuels a good use of land; should food be the priority? And should being the largest trader of sugar be rewarded? Will the climate agenda win the day, or will we see a convergence of climate and food systems considerations? If the listing goes to plan, we should know in early August.